Posts Tagged ‘Rogga’

THE BROKEN EARTH TRILOGY: Five Reasons You’ll Be Glad You Read N.K. Jemisin

I am delighted to introduce this third guest post. Professor Liam Corley, an old friend from my early years as a University pastor at UC Berkeley, writes on Jemisin.

First, Professor Corley will show us why Jemisin is worth reading. Second, he will comment on Jemisin’s deft handling of the story-telling craft. The latter part of the post contains spoilers, but for anyone who cares about writing great characters in epic novels, the professor’s sharp analysis will be incredibly helpful. Enjoy!

Five Reasons…(no spoilers)

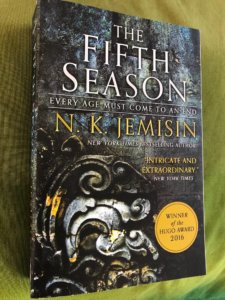

Sure, N.K. Jemisin has won all of the top prizes in the industry, and every one of the books in The Broken Earth trilogy has won the Hugo. But you’re a discerning reader. You don’t follow trends or hype. Why will you be glad you read Jemisin’s amazing novels?

- You’re a mom, and you have fought with your daughter. Maybe been mean. Apologized. Did it again. Jemisin’s work is all about the woman protagonist, especially mothers, and the tangled relationships she depicts will have you thinking about YOUR relationships in a new way.

- You know Black Lives Matter, but you don’t know how to talk about it without bursting into flames or tears. Jemisin’s work is a treasure trove of insight into how to confront, live through, and go beyond racial injustice and all of the horrors it has inflicted. From lynching to the casual use of the N-word, it’s all there, in sci fi clothing.

- You care about the environment–really care–and wonder what humanity is doing to its survival prospects by destroying our home.The Broken Earth faces up to the end of the world. Again and again and again. Why are we destroying the world? Because we’re greedy and hate each other. Yup, that’s pretty broken. But Jemisin also shows people learning how to survive in the aftermath and figuring out how to make things right.

- You think Toni Morrison is the best writer ever. Hands down. Ever. If Octavia Butler and Toni Morrison had a love child, it would be N.K. Jemisin. If you can remember reading Beloved in college or watching the movie with Oprah and bawling your eyes out because it was all just so wrong, so beautiful, and so painfully wrong and beautiful, you’ll want to read The Broken Earth.

- You love great science fiction and fantasy world-building and character-driven plots. If you are an avid sci-fi reader and especially if you write it, you’ll want to immerse yourself in Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy. For more on this point, see my longer review on Craft and Culture in Jemisin’s work below.

Click here to buy the first book of The Broken Earth trilogy. Click here if you want to buy all three.

Warning: there are spoilers below, so in case you haven’t read Jemisin yet, you may want to stop reading and pick up the first book of the trilogy.

Craft and Culture:

Notes on N.K. Jemisin’s The Broken Earth Trilogy

(spoilers below)

Readers of SFF (science fiction and fantasy) have embraced N.K. Jemisin’s acclaimed Broken Earth trilogy, and every installment of the series has won the coveted Hugo Award. Consequently, this post is not meant to introduce new readers to the series. Instead, I will be pointing out elements of Jemisin’s writing that contribute to the magic of the reading experience. Other SFF writers will find this of interest, but so will readers who want to understand why the novels affected them as they did. I’ll touch briefly on how Jemisin weaves her alternating timelines into a narrative fabric that turns flashbacks into a strength, not a weakness, on Jemisin’s incorporation of racial politics that are already part of her reader’s core emotional lives, and on the genres novels’ connections to more literary traditions.

I found myself reflecting on Jemisin’s woven chronologies when I was trying to think through the best ways to incorporate character backstories in my SF work-in-progress. Writers know that flat characters live only in the moment, and their motivations tend to have more to do with survival or accomplishment than working out emotional consequences of their past. Yet providing a character’s past can be a distraction from engaging readers in the drama of the story’s “now” time. How then can authors deepen their characters without losing narrative engagement? Jemisin’s solution is brilliant.

In the first book of the trilogy, Jemisin takes her main character’s timeline and slices it into three parts—childhood, adulthood, and post-apocalyptic adulthood. The character has different names in these time periods and acts in much different geographies and societies, so it takes a while before most readers realize that the chapters which alternate between these three perspectives are actually all the same character at different times of her life. What this allows Jemisin to do is to provide the entire scope of her main character’s life in a nonlinear fashion that is as engaging as it is emotionally excruciating. Getting to know the main character at three very different stages of life gives readers a clear view of the character’s depth, journey, change, and motivation.

This technique shouldn’t simply be adopted wholesale by authors wishing to provide an engaging saga, but it makes evident a point that could be adopted more broadly: backstory needs to be as engaging as the main story or it shouldn’t be indulged in beyond broad strokes and hints. All narrative is a dance between scenes and interludes, scenes and interludes, scenes and . . . Flashbacks, to be compelling and to maintain the hooks of engagement, should be fully realized scenes and not inert paragraphs of backstory.

The Broken Earth series is almost entirely a story about race-based injustice and the ways that civilizations built on exploitation create systems and stories to obscure or recast their dependence on a despised underclass. Jemisin is incredibly effective in evoking readers’ feelings about American racial politics by incorporating parallel dynamics in her fictional world. The first, and probably most overt, instance is her use of a racial epithet, “Rogga,” to indicate orogenes, the enslaved and exploited earth magicians. The sonic similarity of the epithet to the N-word is obvious and intentional. Indeed, even the complex ways the term is used in the series—as slur, as indictment of injustice, as insider labeling—mirror the many ways the N-word is debated in our society. This instance of labeling leaves no questions in the readers’ minds about the allegorical nature of racial politics in Jemisin’s world.

What makes Jemisin’s evocation of contemporary race so powerful is precisely such correspondences that, despite their overt nature when reflected upon, fit so well within plot of the novel that readers can escape the sorts of mental coping mechanisms they have for engaging racial issues in their non-reading lives. Edgar Allan Poe was a master of this technique. His tales of the grotesque and macabre are set far distant in time and geography from the slave-owning Southern states where he lived, but their depictions of torture, fear, guilt, and sadism draw indirectly on the repressed experience of those dynamics on plantations. Jemisin’s incorporation of lynchings, segregation, dehumanization, and other tools used by racist societies to subjugate their victims both draw on and make explicit the prevalence of these practices in our own world.

I’ll pivot here to Jemisin’s relationship to African American literature because the series has numerous plot points and characterizations that evoke masterworks by Toni Morrison, one of the most important American writers of the last century. Morrison has won both the Pulitzer and Nobel Prize in a distinguished career that exploded into prominence with the publication of Beloved in 1988. Morrison’s novels often focus on a strong African American woman character, something Jemisin also does through her allegorical association of orogenic ability with African American identity. [spoiler alert] Several key plot points in The Broken Earth draw on Sethe’s world in Beloved, most notably when Sethe murders her own child to prevent her from being taken back into slavery.

There are at least a dozen other correspondences between Morrison and Jemisin that occurred to me as I read The Broken Earth, but I won’t spoil your reading pleasure by listing them all. Suffice it to say, SFF editors and agents interested in fostering more #ownstories in the genre should expect to see more explicit borrowing from more established traditions in the future. Most importantly, I think that editors and agents should take note of what Morrison and Jemisin already have expressed through their work: #ownstories aren’t niche or sideline stories; they are central to the human condition, and in the case of the United States, foundational to our national identity and culture.

Related to the issue of a society’s foundations in racial injustice, i.e. SLAVERY, is how Jemisin draws on another classic of SFF literature, Ursula K. Le Guin’s immensely powerful and well-known story, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” The story poses a philosophical question about injustice and the related phenomenon of scapegoating: would I live in a society that seemed perfect if I knew its perfection depended upon the suffering a single nameless child? The Broken Earth stages this epiphany and existential crisis time and time again throughout the series, with the added element of the unmerited scapegoating being race-based.

On the whole, I’ve become quite a fanboy of Ms. Jemisin’s work, and I hope someday to assign it in one of my classes on American literature

Liam Corley is a professor of American literature at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. He is also a Navy Reserve officer, and he returned to creative writing as a way of understanding the world after his deployment to Afghanistan in 2008-2009. His work on literature and war can be found in Badlands, Chautauqua, College English, First Things, The Wrath-Bearing Tree, and War, Literature, & the Arts. He is currently at work on a science fiction manuscript about genetics, time travel, and humanity’s irreligious future. He lives in Riverside, CA, with his wife and four children.