Posts Tagged ‘writing’

Writing Facial/Body/Clothing Descriptions, A Study of PD James and a Few Other Literary Giants

Click if you’re looking to read a review of PD James’ The Children of Men.

PD James was a great and popular writer. She was fluent in a particularly upper crusty British style, but could also write gritty stuff (one has to when writing about murder). She also knew how to tell a great story. She used facial descriptions in The Children of Men to transport the reader into her created dystopian world, relying heavily on them to reveal character. Descriptions carried two loads in the novel.

First load carried, character description gives a visual of the character being described. A description of a new character aids the reader as he/she enters the scene and tries to make sense of person being drawn. The reader needs to see the people and the place. Second load carried, character descriptions give the reader a sense of the narrator’s personality. The reader makes judgments about a narrator’s reliability, his/her fairness or prejudices because what details are notable to one person, are not necessarily notable to another. We all know this instinctively. You and I can sit on a park bench and observe the same person for three minutes, go on to describe completely different details about that person. By far, the best way to think about this in writing is to look at how the masters do it.

I took this project on because PD James caught my attention with her colorful and interesting character descriptions.

These are just a handful of examples. All James’ examples are from The Children of Men, the final four will be from Faulkner, Joyce and Trevor.

Theo is the narrator, also the main character in James’ novel, The Children of Men.

After each example, see if you can answer the question:

- What do you learn about this character being described?

- What do you learn about Theo?

Jasper (minor character, one of Theo’s older colleagues, a mentor of sorts): He was the caricature of the popular idea of an Oxford don: high forehead, receding hairline, thin, slightly hooked nose, tight-lipped. He walked with his chin jutting forward as if confronting a strong gale, shoulders hunched, his faded gown billowing. One expected to see him pictured, high-collared as a Vanity Fair creation, holding one of his own books with slender-tipped fingers.

Sir George (minor character, Theo’s uncle and father to the current leader of Britian): But Sir George puzzled my mother. I can still hear her peevish complaint: “He doesn’t look like a baronet to me.” He was the only baronet either of us had met and I wondered what private image she was conjuring up—a pale romantic Van Dyck portrait stepping down from its frame; sulky Byronic arrogance, a red-faced swashbuckling squire, loud of voice, hard rider to hounds. But I knew what she meant; he didn’t look like a baronet to me either. Certainly he didn’t look like the owner of Woolcombe. He had a spade-shaped face, mottled red, with a small, moist mouth under the moustache which looked both ridiculous and artificial, the ruddy hair which Xan had inherited, faded to the drab colour of dried straw, and eyes which gazed over his acres with an expression of puzzled sadness. But he was a good shot—my mother would have approved of that.

Julian (major character and love interest): But at the end of the row was a figure he suddenly recognized. She was sitting motionless, her head thrown back, her eyes fixed on the rib vaulting of the roof, so that all he could see was the candle-lit curve of her neck.

Her hair, dark and luscious, a rich brown with flecks of gold, was brushed back and disciplined into a short, thick pleat. A fringe fell over a high, freckled forehead. She was light-skinned for someone so dark-haired, a honey-colored woman, long-necked with high cheekbones, wide-set eyes whose colour he couldn’t determine under strong straight brows, a long narrow nose, slightly humped, and a wide, beautifully shaped mouth. It was a pre-Raphaelite face. Rossetti would have liked to have painted her.

Old Martindale (minor character/colleague of Theo’s): who had been an English fellow on the eve of retirement when he himself was in his first year. Now he sat perfectly still, his old face uplifted, the candlelight glinting on the tears which ran down his cheeks in a stream so that the deep furrows looked as if they were hung with pearls.

The old priest at St. Frideswide (minor character): He came close and glared at Theo with fierce paranoid eyes. Theo thought that he had never seen anyone so old, the skull stretching the paper-thin, mottled skin of his face as if death couldn’t wait to claim him.

Rolf (major character, Julian’s husband): He had no doubt which one was Julian’s husband and their leader even before he came forward and, it seemed, deliberately confronted him. They stood facing each other like two adversaries weighing each other up. Neither smiled nor put out a hand.

He was dark, with a handsome, rather sulky face, the restless suspicious eyes bright and deep-set, the brows strong and straight as brush strokes accentuating the jutting cheekbones. The heavy eyelids were spiked with a few black hairs so that the lashes and eyebrows looked joined. The ears were large and prominent, the lobes pointed, pixie ears at odds with the uncompromising set of the mouth and the strong clenched jaw. It was not the face of a man at peace with himself or his world, but why should he be, missing by only a few years the distinction and privileges of being an Omega? His generation, like theirs had been observed, studied, cosseted, indulged, preserved for that moment when they would be male adults and produce the hoped-for fertile sperm. It was a generation programmed for failure, the ultimate disappointment to the parents who had bred them and the race which had invested in them so much careful nurturing and so much hope.

When he spoke his voice was higher than Theo had expected, harsh-toned and with a trace of an accent which he couldn’t identify.

Miriam (major character, the midwife): The woman was the only one to come forward and grasp Theo’s hand. She was black, probably Jamaican, and the oldest of the group, older than himself, Theo guessed, perhaps in her mid- or late fifties. Her high bush of short, tightly curled hair was dusted with white. The contrast between the black and white was so stark that the head looked powdered, giving her a look both hieratic and decorative. She was tall and gracefully built with a long, fine-featured face, the coffee-coloured face hardly lined, denying the whiteness of the hair. She was wearing trousers tucked into boots, a high-necked brown jersey and sheepskin jerkin, an elegant, almost exotic contrast to the rough serviceable country clothes of the three men. She greeted Theo with a firm handshake and a speculative, half-humorous colluding glance, as if they were already conspirators.

Gascoigne (minor character): At first sight there was nothing remarkable about the boy—he looked like a boy although he couldn’t be younger than thirty-one—whom they called Gascoigne. He was short, almost tubby, crop-haired and with a round, amiable face, wide-eyed, snub-nosed—a child’s face which had grown with age but not essentially altered since he had first looked out of his pram at a world which his air of puzzled innocence suggested he still found odd but not unfriendly.

Luke (major character, father to the child):The man called Luke, whom he remembered Julian too had described as a priest, was older than Gascoigne, probably over forty. He was tall with a pale, sensitive face and atiolated body, the large knobbled hands drooping from delicate wrists, as if in childhood he had outgrown his strength and had never managed to achieve robust adulthood. He fair hair lay like a silk fringe on the high forehead; his grey eyes were widely spaced and gentle. He looked an unlikely conspirator, his obvious frailty in stark contrast to Rolf’s dark masculinity. He gave Theo a brief smile which transformed his slightly melancholy face, but did not speak.

The old innkeeper (minor character): She was older than he expected, with a round, windburned face, gently creased like a balloon from which the air has been expelled, bright beady eyes and a small mouth, delicately shaped and once pretty but now, as he looked down on her, restlessly munching as if still relishing the after-taste of her last meal.

Carl Inglebach (minor character): He looked—was probably tired of being told so—like a benign edition of Lenin, with his domed polished head and black bright eyes. He disliked the constriction of ties and collars and the resemblance was accentuated by the fawn linen suit he always wore, beautifully tailored, high-nicked and buttoned on the left shoulder. But now he was dreadfully different. Theo had seen at first glance that he was mortally ill, perhaps even close to death. The head was a skull with a membrane of skin stretched taut over the jutting bones, the scrawny neck stuck out tortoise-like from his shirt and his mottled skin was jaundiced. Theo had seen that look before. Only the eyes were unchanged, blazing from the sockets with small pinpoints of light. But when he spoke his voice was as strong as ever. It was as if all the strength left to him was concentrated in his mind and in the voice, beautiful and resonant, which gave that mind its utterance.

Officer Rawlings (minor character): Rawlings, thick-set, a little clumsy in his movements, had a disciplined thatch of thick grey-white hair, which looked as if it had been expensively cut to emphasize the crimped waves at the side and back. His face was strong-featured with narrow eyes, so deep-set that the irises were invisible, and a long mouth with the upper lip arrow-shaped, sharp as a beak.

Aren’t these descriptions delicious? Some might feel PD James goes overboard, but I found myself drawn in and fascinated by the language and the visuals. Each person held a unique place in my mind as the story grew toward its climax.

Just to get a small taste of a few other masters…consider Faulkner, Joyce and Trevor

A Rose for Emily from Collected Stories by William Faulkner

“They rose when she entered—a small, fat woman in black, with a thin gold chain descending to her waist and vanishing into her belt, leaning on an ebony cane with a tarnished gold head. Her skeleton was small and spare; perhaps that was why what would have been merely plumpness in another was obesity in her. She looked bloated, like a body long submerged in motionless water, and of that pallid hue. Her eyes, lost in the fatty ridges of her face, looked like two small pieces of coal pressed into a lump of dough as they moved from one face to another while the visitors stated their errand.”

Lo! From Collected Stories by William Faulkner

“And now the President and the Secretary sat behind the cleared table and looked at the man who stood as though framed by the opened doors through which he had entered, holding his nephew by the hand like an uncle conducting for the first time a youthful provincial kinsman into a metropolitan museum of wax figures.

Immobile, they contemplated the soft, paunchy man facing them with his soft, bland inscrutable face—the long, monk-like nose, the slumbrous lids, the flabby, café-au-lait-colored jowls above a froth of soiled lace of an elegance fifty years outmoded and vanished; the mouth was full, small, and very red. Yet somewhere behind the face’s expression of flaccid and weary disillusion, as behind the bland voice and the almost feminine mannerisms, there lurked something else: something willful, shrewd, unpredictable and despotic.”

Two Gallants, in James Joyce’s Dubliners, a short story collection.

“Corley was the son of an inspector of police and had inherited his father’s frame and gait. He walked with his hands by his sides, holding himself erect and swaying his head from side to side. His head was large, globular and oily; it sweated in all weathers; and his large round hat, set upon it sideways, looked like a bulb which had grown out of another. He always stared straight before him as if he were on parade and, when he wished to gaze after someone in the street, it was necessary for him to move his body from the hips.”

Kinkies, from William Trevor: The Collected Stories.

“In the police station the colours were harsh and ugly, not at all like the colours there’d been in Mr Belhatchet’s flat. And the faces of the desk sergeant and the policewoman were unpleasant also: the pores of their skin were large, like the cells of a honeycomb. There was something the matter with their mouths and their hands, and the uniforms they wore, and the book in front of the desk sergeant were torn and grubby, the air stank of stale cigarette smoke. The man and the woman were regarding her as skeletons might, their teeth bared at her, their fingers predatory, like animals’ claws. She hated their eyes. She couldn’t drink the tea they’d given her because it caused nausea in her stomach.”

There is no perfect way to describe a character, but one learns from the greats. In the case of Faulkner’s A Rose for Emily, one gets a sense of the character being observed, but also a certain judgment by the narrator, a disdain for Emily. And physically, the reader can “see” Emily…her age, weight and height, the fact she is (or was) a person of means.

In the story Lo, one sees the shabbily dressed visitor to the President, but he is a man not to be pitied, as the description closes with the more sinister. This story is fiction, but based in history. George Washington and his aide are the narrators. The quirky man they are describing is Native American, who is requesting a trial for his nephew for the murder of a white man on Chickasaw land. It’s an interesting story, not what you might expect.

In Two Gallants, one sees Joyce’s fluency with language and characterization. To describe any human as having a large, oily and globular head is startling. In fact, it’s almost inhumane the way he continues to describe the hat looking like a bulb growing out of a bulb. This narrator either holds Corly in utter disdain, or the details are meant to hint to the reader that Corly is an unkempt, yet arrogant (given his tendency to “parade”) loser.

In William Trevor’s story Kinkies, can you tell this character has been drugged? There is a sharp paranoia in her descriptions of everything and everyone she sees. Clearly, she is not well and potentially needing help, but the reader can’t imagine her receiving that help in her state of mind.

As a writing exercise, take an image of someone you do not know…an online image is fine…and pen a paragraph about this person. Use these words to steer your description and see how different the observations flow from your pen.

Arrogant:

Grieving:

Insecure:

Cagey:

Expectant:

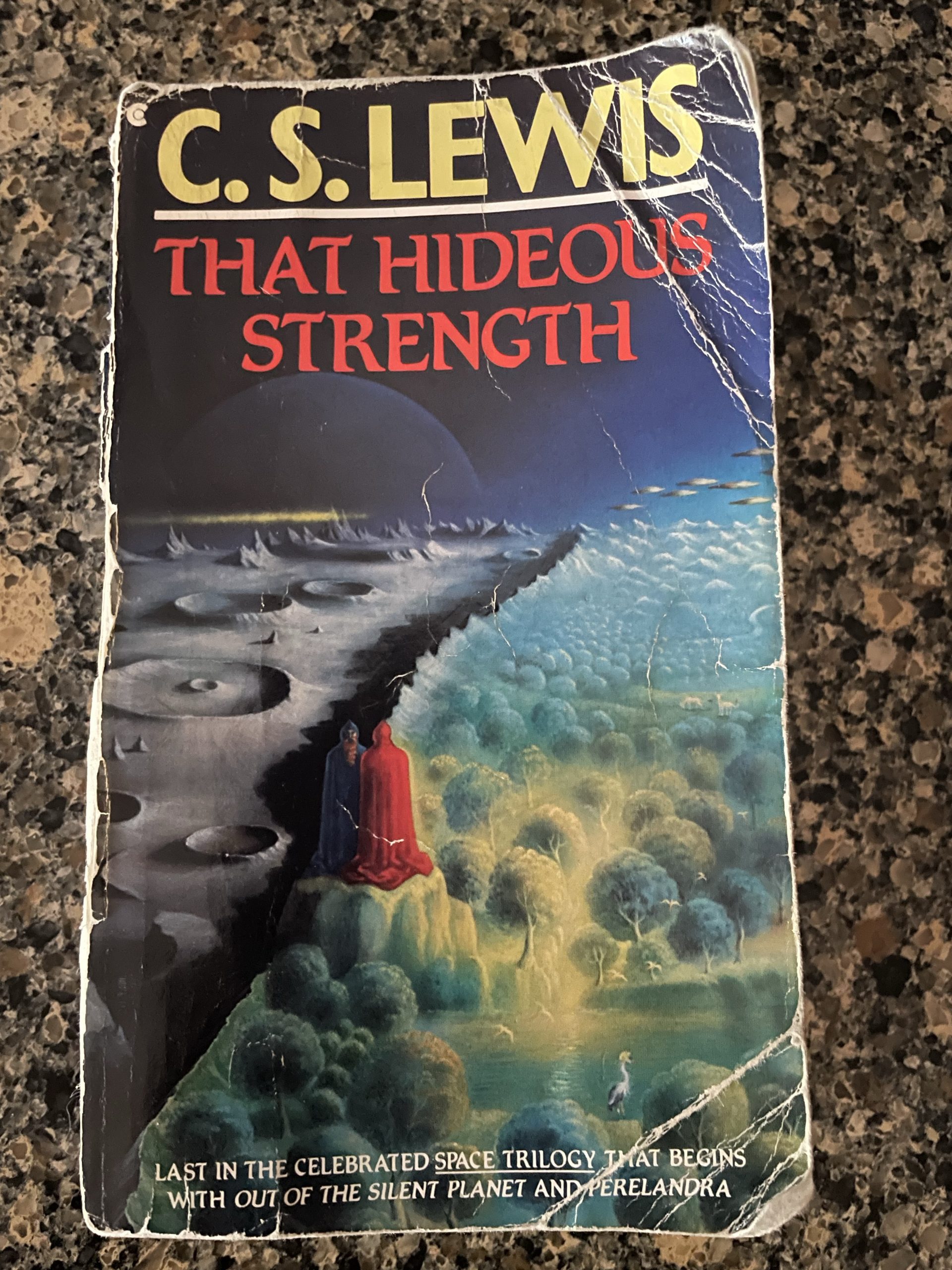

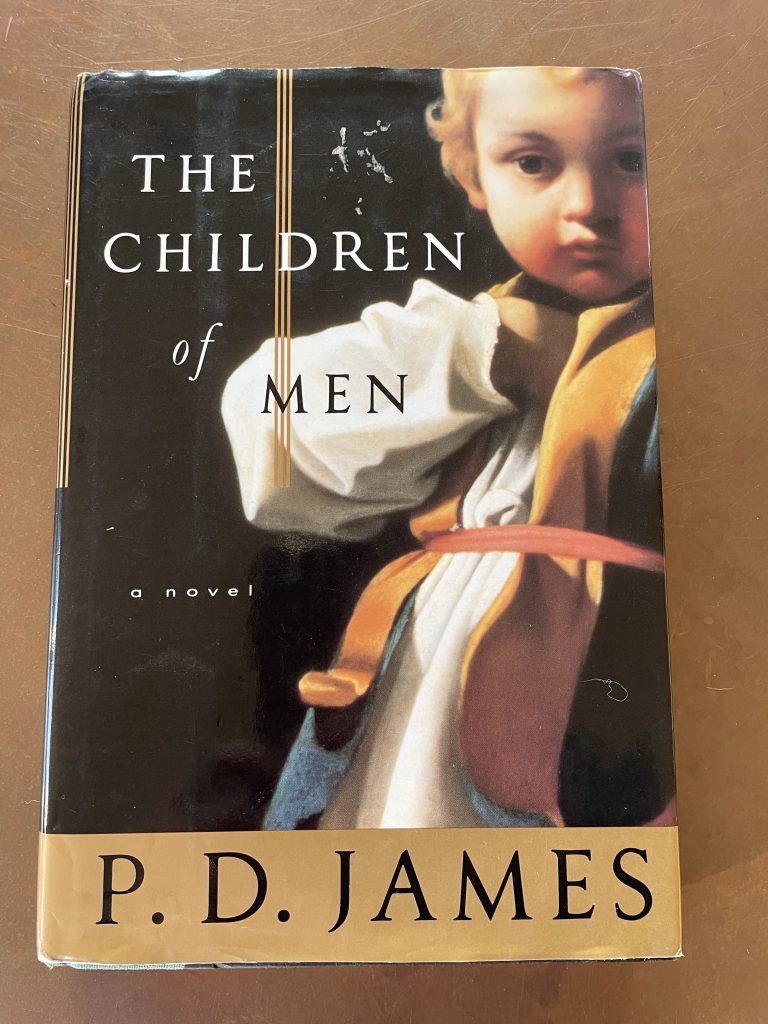

THE CHILDREN OF MEN, A No-Spoiler Review of the novel by PD James

If you’re a person born before 1990, you’ve probably seen the film Children of Men, based on the novel by PD James. I recommend this novel, that falls within the boundaries of science fiction, without reservations. This book is rated PG and appropriate for young adults. The rating is due to adult themes and some violence. I’m guessing it would make a great audiobook…especially if you enjoy listening to British voice actors.

The Short Review. Why read when you can watch the film instead?

- I recommend you do both! I loved the film which adopted the premise of the book, but the novel is unique and interesting in a different way

- Beautifully written

- Decent tension and a mystery to solve

- Subtle ideas about Christianity (Anglicanism in particular) that only partially made it into the film

The Longer Review

Phyllis Dorothy James, Baroness of Holland Park, was a much beloved writer of primarily detective novels. Her first was published in 1962. It was later in her career, in 1992, that she wrote THE CHILDREN OF MEN. While this book is not exactly a detective novel, James unrolls the story with a similar template. She tells the story from the perspective of one man, Theodore Faron. Theo, as he is mostly called in the novel, is a fifty-year old professor of History at Oxford University. More importantly, the backdrop or the world in which he is living is aging and sterile. In the story (all set in England), no one has had a child for over twenty-five years.

The story opens with Theo’s journal entry about the violent death of the “last born” child on earth.

Early this morning, 1 January 2021, three minutes after midnight, the last human being to be born on earth was killed in a pub brawl in a suberb of Buenos Aires, aged twenty-five years, two months and twelve days. If the first reports are to be believed, Joseph Ricardo died as he had lived. The distinction, if one can call it that, of being the last human whose birth was officially recorded, unrelated as it was to any person virtue or talent, had always been difficult for him to handle. And now he is dead.

This book was an interesting read for me as a writer for a couple of reasons, one of which is the wobbly point of view part-way into the novel. First person journal entries in chapter 1-5. At the beginning of chapter 6, Theo grapples with his journal writing as a task in his overly-organized life that gave him no pleasure. So, in this chapter, Theo is still the primary “voice” of the story, but now telling the tale in 3rd person. In chapter 7, he’s back to a journal entry, therefore first person, and in chapter 8 and from here on out, the tale is a close 3rd POV, all from Theo’s perspective. I don’t think the average reader is disrupted by these slight shifts because Theo is still the storyteller. I noticed mainly because novice writers will sometimes shift like this accidentally and most editors would discourage these shifts. James pulls it off because of the “journaling” aspect of the beginning. I think she is using this to show Theo’s passivity. He observes and writes, but does not act. By chapter 8, he has fully made the decision to be a part of the story, not just an observer. He acts as a character in the unrolling narrative and will continue to do so until the end.

Another aspect of James’ writing that I enjoyed were her vibrant descriptions of faces and clothing. Long descriptions seem to be Theo’s favorite way (James’ favorite way) to judge/describe character. Of course, given the descriptions are coming from Theo, they also tell the reader about him. Regardless, I found myself enthralled by some of the descriptions, their length and detail…like this description of Jasper, a minor character and one of Theo’s older colleagues.

He was the caricature of the popular idea of an Oxford don: high forehead, receding hairline, thin, slightly hooked nose, tight-lipped. He walked with his chin jutting forward as if confronting a strong gale, shoulders hunched, his faded gown billowing. One expected to see him pictured, high-collared as a Vanity Fair creation, holding one of his own books with slender-tipped fingers.

Here is Miriam, a midwife and one the primary characters in the second half of the novel.

The woman was the only one to come forward and grasp Theo’s hand. She was black, probably Jamaican, and the oldest of the group, older than himself, Theo guessed, perhaps in her mid- or late fifties. Her high bush of short, tightly curled hair was dusted with white. The contrast between the black and white was so stark that the head looked powdered, giving her a look both hieratic and decorative. She was tall and gracefully built with a long, fine-featured face, the coffee-coloured face hardly lined, denying the whiteness of the hair. She was wearing trousers tucked into boots, a high-necked brown jersey and sheepskin jerkin, an elegant, almost exotic contrast to the rough serviceable country clothes of the three men. She greeted Theo with a firm handshake and a speculative, half-humorous colluding glance, as if they were already conspirators.

Science fiction is not always well-written in the literary sense, so it’s a pleasure to read a book like THE CHILDREN OF MEN, with literary flair on top of a good story.

Regarding the Anglican tidbits. I am a practicing Anglican as of 2018, so I was keying into the references. Theodore (whose name means God-lover) has a distant relationship with the faith of his people, but the reader encounters him coming more alive to this faith even as he moves toward more actions. In the world in which he is living, taking risks and acting, symbolize hope. Hope for a future is what the whole world has given up on. No science and knowledge has been able to solve the problem of humankind’s infertility. The idea of extinction and of God’s abandonment of his creation are stark in Theo’s understanding of the world. There is a beautiful moment, later in the story where a prayer is given from the Anglican book of common prayer over a dead friend.

Theo does the reading.

At first, his voice sounded strange to his own ears, but by the time he got to the psalm the words had taken over and he spoke quietly, with confidence, seeming to know them by heart. “Lord, thou hast been our refuge: from one generation to another. Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever the earth and the world were made: thou art God from everlasting, and world without end. Thou turnest man to destruction: again thou sayest, Come again, ye children of men. For a thousand years in thy sight are but as yesterday: seeing that is past as a watch in the night.”

Theo has awakened to the religion of his youth. It will play a large role in how he manages the final chapters of this gripping story.

THAT HIDEOUS STRENGTH, A Review with Minor Spoilers

The third and final science fiction novel written by CS Lewis, THAT HIDEOUS STRENGTH, is touted by some as a fantasy novel. I hesitate to go deeper to explain why that might be, for fear of spoiling, but let’s just say that the story takes place on Earth, not in space, and one of the key characters who acts in a miraculous and decisive way to defeat the enemy, is a wonderfully fantastical character.

As I have talked with friends who have read all three, I get different answers about which is the “favorite” in the trilogy. There are individuals who love Out of the Silent Planet. I personally like it for its length…it is as short as a novella and a tight little narrative. Others love Perelandra. I appreciate Perelandra, but there are portions where reading was a chore. For me, THAT HIDEOUS STRENGTH is the true novel. It is my favorite of the three.

The Short Review: 5 Reasons I Recommend THAT HIDEOUS STRENGTH

- Compelling main character(s) both grappling with interior life, particularly with identity and faith

- A rich setting, a modern academic world and progressive (Lewis’ words) university leadership that feels creepy, yet familiar

- An amorphous and terrifying villain, well written and historically relevant

- In the midst of the horror, a comedic twist that feels like a Shakespeare switch-a-roo

- A companion novel to 1984. Many minds in this era of the 20th century understood the tyranny of government control. Lewis and Orwell were cut from that same cloth. Warnings that are relevant today and always.

For me, the young married couple, Mark and Jane, makes this story compelling in a way that is unique among the three novels in the trilogy. Jane is a crucial player and well developed. In the previous novels Lewis did not present the reader with a compelling female lead who was relatable. The Perelandra Queen is wonderful, but otherworldly. Jane, in this book, is utterly relatable. Her discomfiture with domestic life, her struggle with a husband who is caught up in his own professional world, felt deeply real. Mark is also real. Lewis highlights his hubris and insecurity, showing the reader how one might choose to align oneself with a horrific community. Mark’s longing for belonging, his hope for recognition are powerful human motivators and have the capacity to diminish the moral spine, especially if that spine is wobbly (as Mark’s is). Despite Mark’s poor choices, I got the feeling that Lewis, like the deity he knows and loves, has not given up on this lost soul. When Mark sinks low enough and faces the worst of himself, there is a promise of redemption.

THAT HIDEOUS STRENGTH is a story with complex layers. The deeper conversation about nations and their “haunting” is a topic I will not cover in this review, but in case you’re wanting to understand more, an article in The Imaginative Conservative called America’s “Logres”: The Mythology of a Nation helped me muse on what might be the American Haunting. That conversation is a crossover of the spiritual and the literary and takes the reader deeper into the mind of CS Lewis and those who were writing in like spirit, JRR Tolkien being one of those writers.

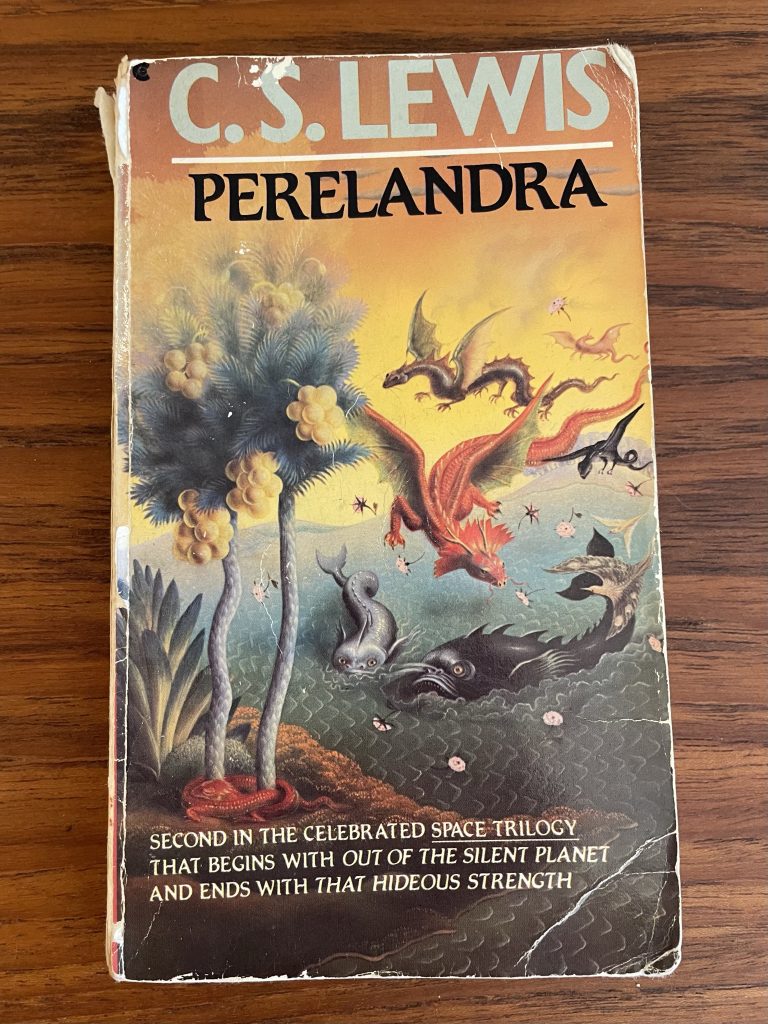

PERELANDRA, A Review

PERELANDRA is the second installment in CS Lewis’ space trilogy. Below is my no-spoiler short review, but the longer review that follows the image of PERELANDRA’s cover, will contain spoilers…beware. This is not a children’s book, but I recommend this novel to all ages who like the story. For all readers, taking the time to discuss after or along the way will deepen philosophical and theological understanding.

Link to OUT OF THE SILENT PLANET for a review of the first book in the trilogy.

5 Reasons to Read PERELANDRA, A Classic Science Fiction Story

- One of the more unique portrayals in literature of paradise and/or a pre-fallen world

- Beautiful CS Lewis prose

- The ideas are put forward clearly and by someone well acquainted with 20th century ideas

- Finally…a strong female character (there were none in the first novel)

- Read all three to make sense of what Lewis was trying to accomplish in the longer narrative arc

3 Reasons PERELANDRA is My Least Favorite of the Trilogy

- There are so few characters and the villain does not arrive until about 1/3 of the way into the book

- Not a lot of drama…there is a slow build and eventually, high drama, but it takes the novel a while to arrive (see #1)

- A lot of speech-making in the final pages. Interesting ideas, but coming at me in my least favorite non-dramatic package

The Longer Review (With Spoilers)

While PERELANDRA is my least favorite of the three books Lewis wrote in the scifi genre, it does have its merits.

For one, anyone who has read his Narnia books, knows how well CS Lewis puts his imagination on the page. He has the ability to create a world both strange and fabulous and took on a bold task to put before the reader a paradise, a pre-civilization and pre-fallen planet with only two human-like people. Basically, he created an Eden. And how would one write this in a convincing way?

This excerpt, one of many examples…just gorgeous.

Now he had come to a part of the wood where great globes of yellow fruit hung from the trees–clustered as toy-balloons are clustered on the back of a balloon-man and about the same size. He picked one of them and turned it over and over. The rind was smooth and firm and seemed impossible to tear open. Then by accident, one of his fingers punctured it and went through into coldness. After a moment’s hesitation, he put the little aperture to his lips. He had meant to extract the smallest experimental sip, but the first taste put his caution all to flight. It was, of course, a taste, just as his thirst and hunger had been thirst and hunger. But then it was so different than any other taste that it seemed a mere pedantry to call it taste at all. It was like the discovery of a totally new genus of pleasure, something unheard of among men, out of all reckoning, beyond all covenant. For one draught of this on earth wars would be fought and nations betrayed.

Elwin Ransom, a professor of philology, is the narrator here. He was also the protagonist in Out of the Silent Planet. In this excerpt, he is telling his tale to a fictionalized version of CS Lewis after returning from his mission to the planet Perelandra. Ransom was sent to Perelandra by the angelic ruler of Mars (Malacandra). The reader is acquainted with this ruler from the previous book. In Out of the Silent Planet, Ransom is kidnapped and brought to Malacandra. That is where he meets Oyarsa, the ruler of Mars. Oyarsa does make an appearance in this novel, as does Weston, one of the academics who kidnapped Ransom in the first story. Weston, the primary rival to Ransom, acts as the tempter in this narrative. He does this not by his own cleverness and strength, but by something more frightening. Weston has given himself over to the bent angelic ruler of Earth, Satan. After Weston arrives on Perelandra in his space vessel, Ransom comes to understand his mission, that he has been sent to thwart the bent Oyarsa by thwarting Weston.

In the story, Weston is an academic with the worst intellectual vices; hubris combined with a flamboyant humanism that borders on narcissism. Tragically, he falls under a true evil in his search of spiritual answers to the mysteries he experienced on Malacandra. Weston’s journey into evil reads like something out of a horror novel (or the Bible).

“Idiot,” said Weston. His voice was almost a howl and he had risen to his feet. “Idiot,” he repeated. “Can you understand nothing?…This is the old accursed dualism in another form. There is no possible distinction in concrete thought between me and the universe. In so far as I am the conductor of the central forward pressure of the universe, I am it. Do you see, you timid, scruple-mongering fool? I am the Universe. I, Weston, am your God and your Devil. I call the Force into me completely…”

Then horrible things began happening. A spasm like that preceding a deadly vomit twisted Weston’s face out of recognition. As it passed, for one second something like the old Weston reappeared–the Old Weston, staring with eyes of horror and howling, “Ransom, Ransom! For Christ’s sake don’t let them—” and instantly his whole body spun round as if he had been hit by a revolver-bullet and he fell to the earth, and was there rolling at Ransom’s feet, slavering and chattering and tearing up the moss by the handfuls…

I was in my thirties the last time I read PERELANDRA and I did not remember how clearly this Weston character gives himself over to evil. Nor did I remember that Ransom comes to the realization that he will have to destroy Weston in hand to hand combat if he is to defeat him.

That Ransom believes he must assassinate his rival provoked my horror. Moreover, the scenes of his battle with Weston are brutal. Lewis does not hold back on that reality, but the idea of this existential battle brought to mind Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Lewis might never have known Bonhoeffer personally, but the ideas Bonhoeffer was writing about and preaching about (in Hitler’s Germany) were likely familiar to him…as they were to every thinking Christian of the time.

Bonhoeffer, while struggling to be a faithful clergy member under Nazi rule in Germany, came to terms with the idea that it was in fact a righteous or just act to kill a man who had fully given himself over to evil. That is why Bonhoeffer was executed in the end, as he played a role in an assassination attempt against Hitler. Below is an excerpt of a sermon on Colossians 3:1-4, a sermon he gave most likely after he had made the decision to collaborate with a part of the resistance determined to assassinate the Fürher.

“Instead, and precisely because our minds are set on things above, we are that much more stubborn and purposeful in protesting here on earth… Does it have to be so that Christianity, which began as immensely revolutionary, now has to remain conservative for all time? That every new movement has to blaze its path without the church, and that the church always takes twenty years to see what has actually happened? If it really must be so, then we must not be surprised when, for our church as well, times come when the blood of martyrs will be demanded. But this blood, if we truly have the courage and honour and loyalty to shed it, will not be so innocent and shining as that of the first witnesses. Our blood will be overlaid with our own great guilt.” (DBW 11, 446) (Schlingensiepen, Kindle Location 2427)

Bonhoeffer’s words evoke the idea that a conservative church is potentially an anemic one. His mention of our great guilt in the sermon I took two ways. One, the church is guilty when it does not act (or waits too long) to stand up to evil. Two, if it does join the revolutionaries, it potentially falls under the guilt of questionable acts. When evil can only be defeated by an act that lays outside of the norm of Christian ethics, there is plenty of guilt to go around. However, Bonhoeffer did not shrink back from taking on that guilt for what he (and history) thought to be the greater good. Moreover, his writings on this remain strong pillars in just-war theory and the Christian struggle with realism versus pacifism.

Lewis travels a similar line of reasoning in this novel and it should not surprise the reader that when the character Ransom leaves the planet Perelandra, he leaves having accomplished his task, but with a wound on his foot that refuses to heal this side of heaven.

THE SILENT SEA, More Brilliance From the Korean Film Industry, A No-Spoiler Review of the Netflix Miniseries

First, the Short Review

6 Reasons I Recommend THE SILENT SEA

- Beautiful production overall, including visuals that underlie the creepy vibe

- Featured a number of my favorite Korean actors, a few you might recognize if Squid Game was on your watch list this past year

- Plenty tension and surprises/frights

- A number of science fiction and haunted house tropes embedded in the story and various characters (see more in longer review)

- The relationships and particularly, the relationship to authority feel authentically Korean. (also, see longer review)

- You know I love the miniseries genre, 1-hour installments of great storytelling that comes to a conclusion without an agonizing cliffhanger

Longer Review

SILENT SEA is the story about a mission to the moon to find water. I rate this series PG-13. No sexual content in this production, but there are dead bodies, and some gore. Family-friendly if your teens are mature. It’s a fun, suspenseful ride.

The first episode quickly gives the viewer the high stakes for this mission. Drought has plagued the Earth. Water is the resource most valuable and due to its scarcity, the planet has become a wasteland. Water is rationed to such a degree, many have suffered physically, billions have died. The wealthy nations have gone into space to find a water source. Most abandoned the idea of finding water on the moon after searching, but the South Korean government kept snooping. There has been a top-secret program at a large moon station that was believed to have borne fruit, but suddenly…the experiment falters. Everyone dies all at once on the moon station. The earthbound directors, including Heo Sung-tae (pictured near end of review) initiate another mission to go to the station and investigate the truth, but secrets pulse underneath the surface of this mission and become one aspect of tension in the story. The authorities hold their cards close and the military and science leaders do not push back, though they suspect something fishy. This may or may not be an aspect of Korean-specific deference to authority, but the screenwriter exploits what I understand as deference in a way that serves the story. Also, this is where the nuanced acting plays such a powerful role in the unfolding of the narrative. The audience can see in the face of Bae Doona, the slight suggestion of twitch, a blink, a stern jaw…we see it, but barely and it helps us know that she understands that she is being deceived. Yet, in most of the outward behavior, she acts the true soldier. Doona is great at this nuanced acting, but she’s just one, among a number of these performers, who pull off such nuance. In my mind, THE SILENT SEA showcases superb writing and better acting than Squid Game. Click for a review of Squid Game

Once the mission lands on the moon, what unfolds reminded me of Ridley Scott’s Alien, in all the best ways. Yes, there will be corpses, tunnels, darkness, betrayals, a terrible and contagious sickness, but there will be one character who keeps her eyes on the prize. Dr. Song (Bae Doona) is intent on discovering the truth. In part, she seeks the truth because her sister is one of the corpses and the holder of many of the secrets. Doona as Dr. Song, pictured above, is a female lead in the Korean zombie series, Kingdom. To see my review of Kingdom, click here

I beat this drum a lot but I do feel that Netflix streaming continues to find the best international productions and when it comes to science fiction, the Korean film/media community is putting out a lot of great product. Produced by Jung Woo-sung, directed by Choi Hang-Yong, who deftly handles the brilliant storytelling of screenwriter, Eun-Kyoi Park. Honestly, I think I could teach a five-hour course on writing with this series, moving scene by scene through the screenplay, in terms of a classic sci-fi thriller. Fun fact, this story (as did Scott’s Alien), closely follows the haunted house template. That means there are a few predictable tropes. The audience knows that the mission is doomed (at least the mission as it was originally conceived) as one by one, the team gets whittled down. Who will remain in the end…that is what the audience wonders. Regarding the various characters, the majority of them hold their own, each having his/her own arc, including the wise-cracking military scrub who just wants to go home…a longing the audience suspects will not be realized.

I highly recommend. THE SILENT SEA, and suspect that Netflix now has me pegged in its algorithm as a person who loves Korean-produced thrillers/sci-fi. I might need to give the Koreans their own category on my site. The product is so good, I can’t stop watching and when I watch, I always review.

THE HOBBIT, Chapter 1…A Study on Craft

For educators: This post and others like it are appropriate for a student who wants to improve in storytelling and/or writing stories. However, most of my writing posts contain spoilers. I recommend the student read the book first.

This is my second installment on first chapters. A few days ago, I analyzed chapter 1 of DUNE. To read that post, click here. Today, I analyze chapter 1 of THE HOBBIT.

This first chapter

–introduces the reader to the world and the main characters

–evokes reader empathy for Bilbo by showing Bilbo’s inner conflict

–presents the choice that will change Bilbo’s life forever

–introduces the reader to the fantastical possibilities that lie ahead, but also the dangers

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.

Thus begins THE HOBBIT, by J.R.R. Tolkien, but really this sentence begins the longer saga that so many have come to know and love, THE LORD OF THE RINGS. Notice what it accomplishes.

- Sentence #1 introduces a new creature, the hobbit. This creature will inhabit the long saga. Bilbo first will be the unlikely hero (later his nephew, Frodo takes over the hero’s mantle). The audience will come to admire, adore and identify with Bilbo and Frodo.

- This sentence begins to describe the culture of hobbits. They are earthy, living in holes, but absolutely committed to cleanliness and comfort. These creatures are civilized…they just happen to like holes as their place of abode.

- In this first sentence, Tolkien begins to evoke our empathy for Bilbo, who will soon trade in his life of comfort for a wild and magical adventure.

Paragraph #2 of THE HOBBIT describes Bilbo’s home in detail, which will be the place where all the action takes place in the remainder of the chapter, including the entertaining of a wizard and a large group of dwarves, but even more than that, this home represents the comfortable life of a gentleman. Later in the story, Bilbo often longs for home (as does Frodo in the LOtR saga) as a place of rest, comfort and peace. It is a place to return to.

Paragraph #3 and #4 describe Bilbo’s ancestry, posing the curious conflict he bears within himself. There is a debate between the Baggins and the Took within Bilbo. The Took side of his family (Bilbo’s mother’s side) is prone to adventure and risk-taking. The Baggins side of the family (Bilbo’s father’s side) is conservative and would reject adventure and any controversy at all. The reader doesn’t have to wonder for very long which side will win out. Without that Tookish spirit, Bilbo might never have walked away from his comfortable hobbit hole.

Both impulses inhabit Bilbo and most readers can relate. It might be said that opposing impulses, such as what Bilbo experiences, are a part of every person. Thus, Tolkien evokes our empathy for Bilbo in chapter 1. Much as Bilbo leaves the comfort of his hobbit hole to journey with the dwarves, the reader leaves his/her comfort to embark with them in the story world.

Now for the rest of chapter one: Bilbo, because he values hospitality, entertains Gandalf (a wizard who believes Bilbo will be a key member of the adventure) and a group of dwarves who demand food, drink, then compel him to travel with them to a place where a dragon guards a great treasure. The adventure, as it is presented, is magnificent, romantic and promises great wealth. Bilbo is taken in, though it is touch and go for a while whether or not he can bring himself to leave his Hobbit hole. Despite his willingness to leave his home, it could be said the hobbit is in a way bewitched by the romantic notion of a grand adventure.

As they sang the hobbit felt the love of beautiful things made by hands and by cunning and by magic moving through him, a fierce and jealous love, the desire of the hearts of dwarves. Then something Tookish woke up inside him, and he wished to go and see the great mountains, and hear the pine-trees and the waterfalls, and explore the caves, and wear a sword instead of a walking-stick.

Yet, Thorin, the lead dwarf, does not mince words about the dangers they might face.

We shall soon before the break of day start on our long journey, a journey from which some of us, or perhaps all of us (except our friend and counsellor, the ingenious wizard Gandalf) may never return. It is a solemn moment.

What is Bilbo’s reaction to this sobering news?

Poor Bilbo couldn’t bear it any longer. At may never return he began to feel a shriek coming up inside, and very soon it burst out like the whistle of an engine coming out of a tunnel. All the dwarves sprang up, knocking over the table.

The stage has been set. The semi-cowardly and ill-prepared Bilbo Baggins will reluctantly leave his comfortable hobbit hole and venture with these new friends, the dwarves and Gandalf. When he finally returns, he will be completely changed and so will Middle Earth.

For over the misty mountains cold

To dungeons deep and caverns old

We must away ere break of day

To find our long-forgotten gold.

Bilbo went to sleep with that in his ears, and it gave him very uncomfortable dreams. It was long after the break of day when he woke up.

This stanza, when one reflects on THE HOBBIT and THE LORD of the RINGS speaks of long-forgotten gold. The dwarves believe this to be part of their hoard, that which is guarded by the dragon, Smaug. The reader understands a deeper meaning. Long-forgotten gold is the one ring to rule them all, found by Bilbo…later passed on to Frodo, becoming the impetus for the Lord of the Rings Saga.

The reader doesn’t understand at this point the profundity of the dwarves’ song, but it is there, imbedded in that first chapter of the very first book.

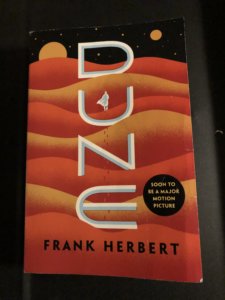

DUNE, Chapter 1. A Study on Craft

For educators: This post is appropriate for teens who have read Dune and might want to to improve their storytelling/writing skills.

I happen to be in a writing critique group that started up this past week. A couple of the folks in this group are writing novels and sent in first chapters for a swipe at getting feedback. So, I read a few first chapters yesterday and in the course of my reading, I began to wonder…Do these seem like first chapters to me? How do I feel as a reader as I am taking in the narrative for the first time? Do I begin to have a strong sense about the story, the characters and about the writing style? Absolutely. I did and do have feelings and ideas. Some of those made me want to keep reading. Others did not.

That led me to the question: How does a novelist write a brilliant chapter one that makes you want to keep reading?

I wonder about my own first chapter, the beginning of my novel that is undergoing an extensive edit. What is it accomplishing and what is it not accomplishing? Have I done the necessary work to hook my reader, keep them interested and engaged, settle them into the world I am creating?

All writers of any genre ponder this question when they sit down before the blank page because the possibilities are endless, as endless as stories themselves. However, I do think there are ways to understand first chapters, to critique and edit them for the purpose of making them better.

Therefore, I begin a series of posts devoted to the question of beginnings. My focus will be on science fiction and fantasy novels and the hope is not to be prescriptive. Telling the writer what to do or not do detracts from originality and art. However, paying attention to how great authors craft a narrative is worthwhile. We learn from the greats. Study enough greats and we begin to see common threads.

So, my goal in this series of posts is to plunder first chapters and see what I can glean about my own writing and will record my findings for the sake of other writers.

A Look at DUNE, Chapter 1

A Look at DUNE, Chapter 1

Frank Herbert is a great writer and though the novel DUNE isn’t perfect, it’s very close to perfect. How does that first chapter set us up for a marvelous journey?

I see it accomplishing four things.

Chapter 1…

-Gives us a sense of the setting in which the story will take place

-Introduces the primary characters, even putting the main character through a first test

-Hints at the coming conflict

-Tantalizes the reader with compelling mysteries that make you want to keep reading

Chapter 1 of DUNE give us a sense of the setting.

Here is the first sentence of the novel.

In the week before the departure to Arrakis, when all the final scurrying about had reached a nearly unbearable frenzy, an old crone came to visit the mother of the boy, Paul.

Most of us have experienced moving houses, cities, states. We know what it feels like to change locations. In this first sentence of DUNE, the reader is alerted immediately to the fact that a change in location is taking place for this particular family, for this particular person, Paul. Moving is disruption. Paul’s family is about to be disrupted. He will soon be leaving Caladan for a planet called Arrakis, sometimes called Dune.

Soon after, in the early paragraphs, Herbert repeats this series of words three times as paragraphs. They jump out on the page like a refrain. They are written in italics, which in Herbert’s style, represents thought. Paul, the main character continues to mull over this reality.

Arrakis—Dune—Desert Planet

So, not only will Paul be leaving his current location, but the new location is harsh. There is a sense of foreboding about this desert planet. Paul will move from Caladan, a land where water is plentiful to Arrakis, where water is scarce. Caladan is known, comfortable, secure, a virtual paradise. Arrakis is mysterious, uncomfortable in so many ways, in part because of its climate. Climate will be a large issue in the rest of the novel. Herbert wants the reader to begin thinking about ecology and its importance to a planet and a people.

Here is the second sentence of DUNE.

It was a warm night at Castle Caladan, and the ancient pile of stone that had served the Atreides family as home for twenty-six generations bore that cooled-sweat feeling it acquired before a change in the weather.

When Paul’s family leaves Caladan, they are not only leaving their current comfortable home/castle, but they are leaving their home of twenty-six generations. This move is an epic move. The reader is left asking…why? Why leave this lovely planet and this home of so many years? We get a few clues as to why this move it taking place. Power and political maneuvering are introduced, a profound subject of the story.

Thufir Hawat, his father’s Master of Assassins, had explained it: their mortal enemies, the Harkonnens, had been on Arrakis eighty years, holding the planet in quasi-fief under a CHOAM Company contract to mine the geriatric spice, mélange. Now the Harkonnens were leaving to be replaced by the House of Atreides in fief-complete—an apparent victory for the Duke Leto. Yet, Hawat had said, their appearance contained the deadliest peril, for the Duke Leto was popular among the Great Houses of the Landsraad.

Arrakis is the place where the empire derives its most important resource: Melange, or spice, as it is sometimes called. Melange is the secret to space travel in this particular universe.

We can already see now how the chess pieces are stacking up, a sense of the conflict.

This brings us to the second accomplishment of Herbert’s chapter one, the introduction of most of the main characters.

Paul is mentioned in the first sentence. So is his mother. Paul’s mother and Paul are on the stage for the very final scene of the novel as well. In fact, his mother gives voice to the final paragraph/speech.

Not only that, but the crone mentioned in that first sentence, the one who will test Paul later in the chapter, will also be on that stage at the finale. This is great writing.

Add to the list the Bene Gesserit, the Fremen, House Harkonnen…all are mentioned, Thufir Hawat, (who will be present in the final scene) and Dr. Yueh, important as the one who betrays House Atreides…all are introduced in chapter 1.

Note this paragraph early in the chapter.

Paul awoke to feel himself in the warmth of his bed—thinking…thinking. This world of Castle Caladan, without play or companions his own age, perhaps did not deserve sadness in farewell. Dr. Yueh, his teacher, had hinted that the faufreluches class system was not rigidly guarded on Arrakis. The planet sheltered people who lived at the desert edge without caid or bashar to command them: will-o’-the-sand people called Fremen, marked down on no census of the Imperial Regate.

The Fremen will become important to the story, of primary importance, but the reader is simply introduced here. There is mystery surrounding these people. I am curious. I want to learn more and Herbert will plunge me into Fremen culture before too long.

It’s interesting to note who is left out of chapter 1.

Chapter 1 hints also at future conflict.

As Paul is undergoing the test, the gom jabbar, here is what the Reverend Mother, the crone says to him.

The old woman said: “You’ve heard of animals chewing off a leg to escape a trap? There’s an animal kind of trick. A human would remain in the trap, endure the pain, feigning death that he might kill the trapper and remove a threat to his kind.”

As I was re-reading the chapter last night, this nugget stopped me in my tracks. I had not realized, not seen how this Reverend mother quote foretells the remainder of the story.

Paul does feign death on Arrakis, so that he might kill the trapper and remove the threat to his family. That is, in essence, a summary of the novel. These two sentences are so brilliantly placed, subtle in all the best ways. We don’t understand consciously upon first reading, but Herbert has just told us what we can expect.

Lastly, chapter 1 teases the reader with mysteries.

This is an odd world, a mysterious one in which a mother of an only son, will give him up to a religious figure, knowing he might die.

Jessica stepped into the room, closed the door and stood with her back to it. My son lives, she thought. My son lives and is…human. I knew he was…but…he lives. Now, I can go on living.

This we absorb and I, at least, want to read to find out more about this bizarre world where such a thing would happen. In order to know more, I must keep reading.

Then, there is the planet Arrakis and the Fremen. In chapter one, we learn very little about them, but we wonder about them as Paul does. The planet is a desert and the Fremen seem to live off the grid. They are wild and uncounted by the empire. Who are they? We are meant to wonder, and to find out, I have to keep reading.

And lastly, in Chapter 1, Herbert introduces the reader to the idea of the Kwisatz Haderach, a messianic figure. Is Paul the Messiah? The reader suspects he is, though Paul himself struggles with this identity throughout the novel, mysterious even to him. We will have to keep reading if we want to figure out the true identity of the Kwisatz Haderach.

So…all of this in Chapter 1. I am wowed and I am hooked. I am also set up well in the world to take in more of the details as they unfold. Moreover, I have enough sense of the main characters to be able to navigate this complex world where many more characters will soon be introduced. It makes me wonder how many times Herbert went back to edit and perfect his beginning…because I don’t think he could have written a better version than the one we read today.

DUNE, A Review of the Novel

DUNE, the novel holds up well to post-modern scrutiny and the writing is mostly perfect.

This is a PG-13 story, for sexual and violent themes, although those scenes are not explicit in this novel.

The Short Review

5 Reasons the Science Fiction Fan Needs to Read this Book Now

- DUNE, the film will be released in 2021…at least the first film of two will be released…unless pandemic interferes. In this case as in most, I recommend reading before viewing

- Compelling villain and compelling hero, with complex motives for each

- Dynamic characters around the main character, including a number of strong females

- Among the best world-building you will find in science fiction

- Without simplifying the complexity of good versus evil, this story gives the reader a vision of truth, goodness and honor

The Longer Review (mini spoilers below):

When George Herbert created the character Paul Atriedes, he stumbled upon a savior-type, a hero, a character who could embody a kind of leadership that most of humanity longs for. Hero stories are nothing new, certainly not new to the science fiction audience, but great ones are to be treasured.

In the case of DUNE, Paul is not the only treasure. The people of the planet Arrakis, the Fremen, also embody an ideal. They are oppressed, but intelligent, pushed to the margins of society, but resourceful and willing to sacrifice for the cause. Their discipline is akin to the greatest armies of literature and history. They are as creative as tenacious as a Roman legion, as fierce as Khan’s Mongols and as disciplined as the Spartans.

(Spoiler here) So what is supposed to get under our skin about DUNE? How can one argue with a story where the overly confident and utterly powerful Emperor is outsmarted, out-gunned and defeated by an honorable and humble tribal people? That feels so right and good.

But there are complexities that go along with this storyline. Paul is not as pure a hero as he might seem. His role as Messiah is an idea that plagues him throughout the novel because he knows he is not simply fighting for the Fremen. He is also motivated by vengeance and honor. He uses the Fremen to avenge his father, so his victory is an uneasy one. Even as he negotiates a marriage to the Emperor’s daughter for status and honor, but keeps his Fremen lover as concubine, the audience sees the inherent politics that will inhabit Paul’s governing. How Paul will rule the Empire is a story for later books, but the seeds of the struggle are sown well and deep in the original novel. So, even as the audience breathes relief at the victory over injustice, there is more to ponder.

To purchase the novel, click DUNE

There is also an amazing graphic novel version which is being released book by book. Dune is made up of three sections, called books. The first installment in graphic novel form is available here. To purchase, click DUNE, Graphic Novel The second installment will be released in the Spring of 2022. No date yet on the third and final.

Lastly, the 2021 theatrical trailer is out and worth a view, perhaps best seen after reading the novel…but then, maybe not.

Click here to see DUNE, film trailer

So, You Just Finished Writing a 70K Word Sci-Fi Novel…Advice to the Young Writer

So, I had the phone conversation with a young man (son of an old friend) yesterday. I decided to write him a follow up email with a few resources I have appreciated and it made sense to put it into a post. Next time, I can just send the link. Actually…I wouldn’t do that. I would still take the phone call, but it helps to have the information written down in one place.

For the new writer…Here’s my advice:

First, congratulate yourself that you just wrote a novel. That.Is.Amazing. Celebrate and then think like a critic and move on. Try to figure out if this book is what you really want to publish and to the best of your ability, think about whether or not you’re addicted to writing. If you’re not, the road is too hard and very long (for most of us). Don’t keep going unless you know you really LOVE it.

Social Media. You might hate it, but every author has to be on social media. If you want to start somewhere, try Twitter.

On Twitter, connect with and start following folks from the #WritingCommunity. Other hashtags you could check out: #amwritingsciencefiction, #amwritingspeculativefiction, #amwriting, #amwritingfiction. While you’re there you’ll find links to various author websites. Some are way more amazing than mine, others are just a page with a photo and the book cover, with minimal links if any. Begin thinking about your author website. How do you want it to feel? What content, if any, do you want to regularly produce on it?

Find a Critique Group:

It’s great to have beta readers, but it’s even better to find a group of writers, like-minded souls who write and will be willing to read your stuff and give you feedback. I’ve started a number of groups over the years. What I have found is that the most important trait for those in the group is work ethic. If the people aren’t actually writing, then it’s probably not worth your time because A. they won’t submit anything to the group and B. They will be the weakest when it comes to critique. Find people who write and be willing to put in the work for them by being a thorough and honest critic. Work for them and they will work for you. (That’s ideal…always exceptions, but be careful about those exceptions).

Go to Cons (like Emerald City Comic Con or WisCon) and get to know people. You will meet fans and you will meet writers and small publishers. You will make connections and you will have fun. (Photo of Ariel is my daughter, who goes to Cons and always dresses up, mostly not in Disney costumes, but this was the best photo I could find today…plus, it’s bright and cute.)

Books on writing and why I like them:

Story: Structure, Substance, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee

If you buy one book, I would make it this one. I’ve taken McKee’s class twice (weekend course) and everyone from Pixar would attend in the Bay Area (where I used to live). Screenwriters would fly up from LA to take it in case they had missed the weekend in Southern California. I knew writers who would take it every other year during the time he was touring. He traveled all over the world teaching his course in the 90s and early 2000s. Why? I think he had/has a way of distilling what it takes to tell a great story. It’s less literary and more about structure, the architecture of good storytelling. I refer to this book all the time, also because this was the stuff I never learned in college. For whatever reason, my writing program de-emphasized story structure. Maybe they thought we were smart enough to pick it up, sniff it out and do it ourselves.

*Why don’t I have a photo of this book cover? I have loaned it out…which so many of us writers inevitably do and then regret. That book has escaped my shelves. I have no idea who has it now, so I will probably have to buy it again. DRAT! It’s not cheap!

Steering the Craft by Ursula K. le Guin

le Guin has written a wonderful series, 5 fantasy books (long before Harry Potter) about a wizarding school, called

If you don’t want to buy all five, try out the first one.

UK le Guin is one of my heroes. Here is my review of her science fiction book, THE LEFT HAND OF DARKNESS, A Book Review

The ART of Character by David Corbett

This book (pictured on the top of post) drives home the kinds of techniques that make characters eternal/memorable. It too is practical. The chapter on Protagonist Problems is spot on and one of the best things you can read as a young writer. Corbett captures key mistakes many writers make when crafting characters, especially main characters.

Revising Fiction, by David Madden

Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of 2019. Worthy of a Post. Worthy of Purchase.

Writes editor John Joseph Adams…”The BEST AMERICAN SERIES is the premier annual showcase for the country’s finest short fiction and nonfiction. Each volume’s series editor selects notable works from hundreds of magazines, journals, and websites. A special guest editor—a leading writer in the field—then chooses the best twenty or so pieces to publish. This unique system has made the Best American series the most respected—and most popular—of its kind.”

To order this anthology, click Best of SFF 2019.

LaShawn’s story was first featured here…but why just read hers…there are so many great stories in this anthology.

https://www.apex-magazine.com/sister-rosetta-tharpe-and-memphis-minnie-sing-the-stumps-down-good/